Harper's Weekly

November 14, 1891

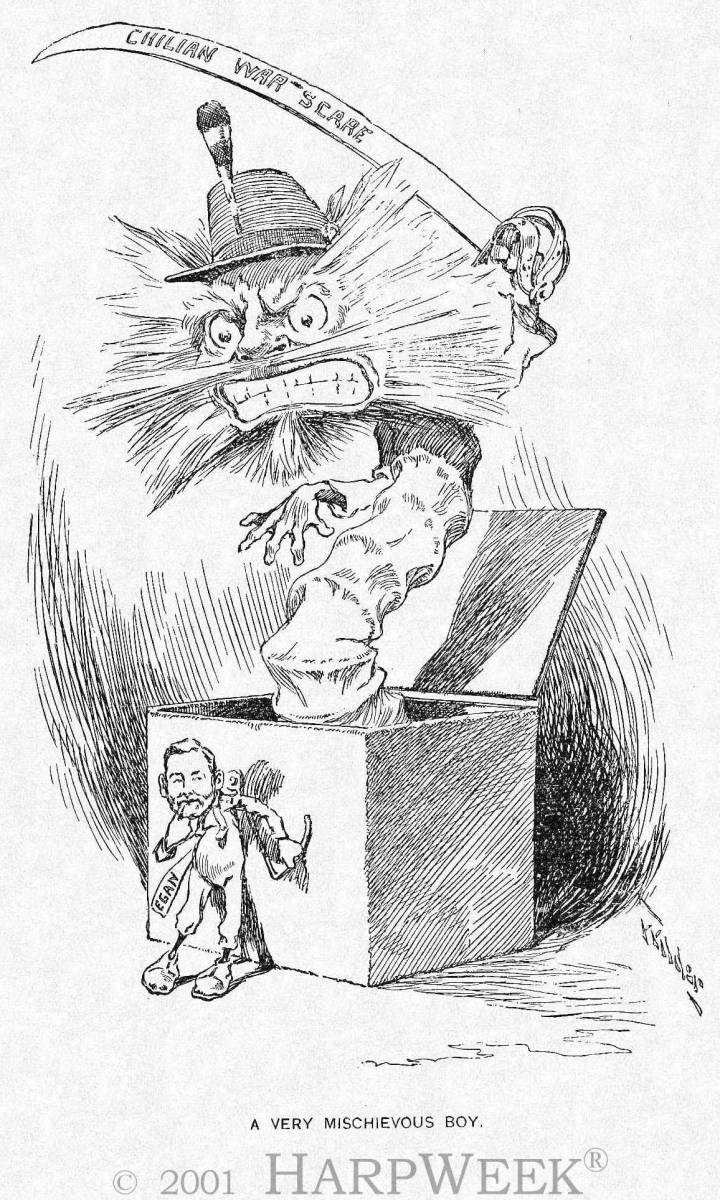

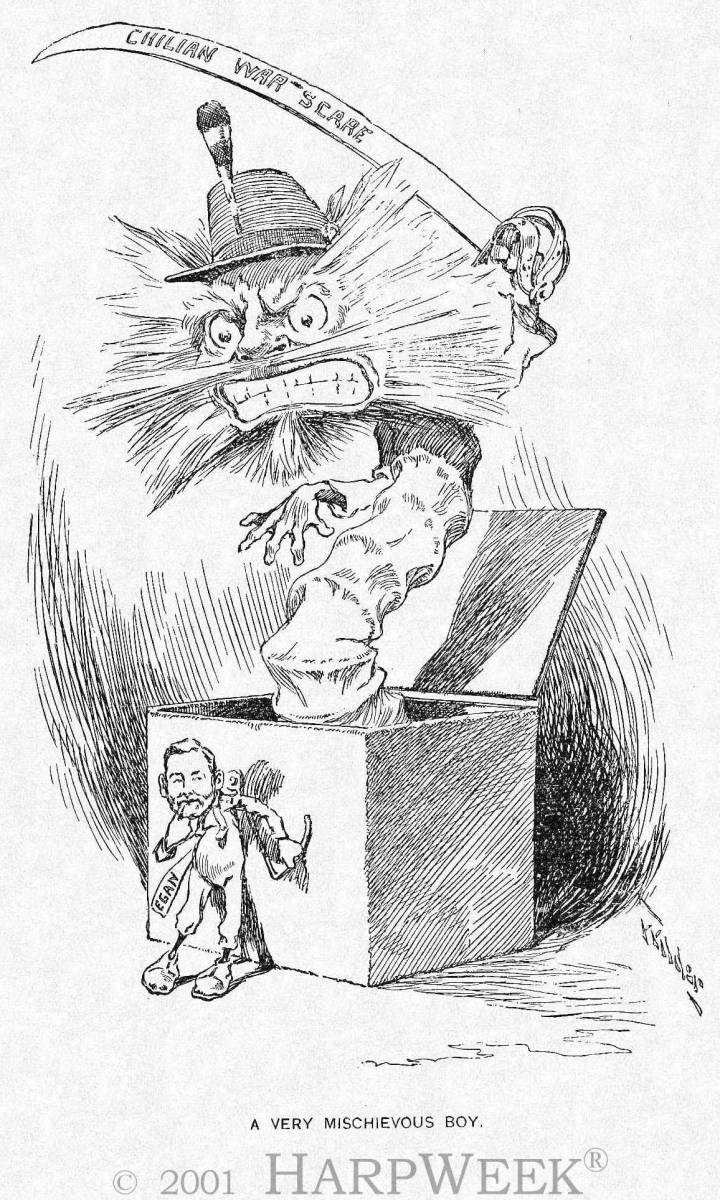

A Very Mischievous Boy

Artist: Herbert Merill Wilder

Harper's Weekly

November 14, 1891

A Very Mischievous Boy

Artist: Herbert Merill Wilder

On October 16, 1891, outside the True Blue Saloon in Valparaiso, Chile,

a brawl between American sailors and Chilean nationals resulted in two

American sailors killed, 17 wounded (five seriously), and many arrested.

The

incident sparked a diplomatic crisis that lasted for months, occasionally

threatening war between the two countries, until a settlement was reached

in

early 1892. The featured cartoon blames Patrick Egan, the U.S. minister

to

Chile, by portraying him as a mischievous boy who has cranked up a

menacing Jack-in-the-box, which wields a sword labeled “Chilian War

Scare.”

Tension in the U.S.-Chilean relationship dated back at least a decade to

the

tenure of James G. Blaine as secretary of state under Presidents James

A.

Garfield and Chester Arthur (March-December 1881). Blaine had supported

Peru against Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879-1884), charging that

Chile’s military aggression was encouraged by Great Britain. Hoping

to

enhance American trade in Latin America, Blaine criticized British economic

interests in Chile. Chileans nationalists shared Blaine’s anti-British

sentiment,

but distrusted the American secretary’s motives. Chile and the United

States

were also on a collision course because influential elements in each hoped

to

make their respective country the dominant power in South America.

In March 1889, President Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893) named Blaine

secretary of state. Blaine was pleased to find that the new Chilean

president,

José Manuel Balmaceda, was seeking to undermine British influence

through a

nationalistic campaign of “Chile for Chileans.” To further “twist

the [British]

Lion’s tail,” the secretary of state named Patrick Egan as the U.S. minister

to

Chile. Egan had fled Ireland in 1882 when the British government

issued an

arrest warrant against him for alleged crimes committed in the service

of Irish

independence. In the United States, Egan obtained American citizenship

and

backed the political aspirations of Blaine (who was the Republican

presidential nominee in 1884).

When civil war erupted in Chile in early 1891, the United States threw

its

support to the Balmaceda government, while Britain backed the rebel faction

called the “Congressionalists”. In May 1891, the U.S. government

responded to a request from the Balmaceda government to apprehend a rebel

Chilean ship, the Itata, which had loaded a shipment of arms in San Diego,

California. The Congressionalists won the civil war, and the Harrison

government released the ship in July and recognized the new Chilean

government in August.

Tensions remained high, however, and the U.S. Navy Department considered

contingency plans in case of war. Part of the friction stemmed from

Egan’s

grant of asylum in the American mission to several leaders of the defeated

Balmaceda faction. By October, only 15 of the original 80 refugees

remained

at the mission, but Egan refused an order from the Chilean government to

surrender them. In response, the Chilean secret police surrounded

the

building to prevent the refugees’ escape.

On October 16, the captain of the U.S.S. Baltimore gave shore leave to

117

American sailors in Valparaiso, Chile’s second most populous city and an

important port. Later that day, an altercation between an American

sailor and

a Chilean sailor escalated into a riot involving numerous sailors, boatmen,

longshoremen, and townspeople. Both sides blamed the other for initiating

the violence, but American sources suspected a planned assault on American

sailors.

President Harrison, already angered by the refugee dispute, became furious

over the Baltimore affair. The United States government demanded

“prompt

and full reparation,” but the Chilean foreign minister, Manuel Matta, promised

nothing until the judicial process was completed. Secretary of State

Blaine,

who had been absent since May due to illness, returned to duty on October

26 and, to his critics' surprise, urged caution and patience during the

diplomatic crisis.

The situation cooled somewhat for several weeks until a war of words

erupted in early December. In his annual address to Congress, President

Harrison blamed Chile for the Baltimore affair and criticized the “offensive

tone” of Chilean foreign minister Matta. Navy Secretary Benjamin

Tracy

echoed the president’s sentiments. Matta responded publicly on December

11 by declaring that the American government was insincere, wrong, and

bellicose. That further incensed Harrison, and Egan broke off communication

with the Chilean government, which intensified its surveillance of the

American

mission.

Harrison stepped back from the brink of war when Blaine insisted that no

additional demands be made immediately on Chile, and when a newly

installed Chilean administration replaced Matta on January 1, 1892, with

a

more conciliatory foreign minister, Luis Pereira. Pereira met cordially

with

Egan, the secret police were removed from the American mission, and the

refugees were allowed to leave the country without arrest. On January

8, a

Chilean court indicted three Chileans and one American for their involvement

in the Baltimore affair.

With an end to the diplomatic dispute in sight, on January 20 the new Chilean

government ineptly called for the removal of Egan as U.S. minister.

Harrison,

this time with Blaine’s approval, sent a strongly worded message to Chile,

rejecting the Chilean court’s findings, calling the Baltimore incident

a

deliberate attack on uniformed American servicemen, refusing to discuss

Egan’s position, and demanding “a suitable apology and … adequate

reparation for the injury done to this Government.”

On January 25, the Chilean administration, warned by European ministers

that

the Americans were poised for war, conceded all points. In February

1892,

a Chilean court handed down prison sentences for the three indicted Chilean

rioters, and in July the Chilean government offered to pay the United States

$75,000 in reparations, which the Harrison administration accepted.

Egan

remained as the U.S. minister until fired by President Grover Cleveland

in

1893 after he again offered asylum during another Chilean civil war.

Robert C. Kennedy