January 10, 1874

Since 1868, Cuban rebels had been fighting for independence from Spain

in a

guerrilla war which would last until 1878. Many Americans sympathized with

the Cubans, and a few fought alongside them as mercenary soldiers. The

Virginius was a ship captained by Joseph Fry, an American soldier of

fortune, which was used in an attempt to smuggle arms to Cuban rebels.

It

sailed fraudulently under the neutral American flag and carried counterfeit

American registration.

On October 31, 1873, the Virginius was captured by Spanish officials in

international waters, and 36 crew members and 15 passengers, including

several American citizens and British subjects, were executed. The story

made headline news in the United States, with commentators calling for

the

administration of Ulysses S. Grant to take swift action. Rumors circulated

widely, and large crowds at public meetings across America called for war.

Secretary of State Hamilton Fish directed Daniel Sickles, the U.S. minister

to

Spain, to demand restitution from the Spanish government, and to close

the

embassy and leave the country if Spain did not meet the demand within 12

days. Sickles delayed his departure by one day, and on November 27, 1873,

Spain agreed to release the ship and its survivors. In 1875, Spain paid

an

indemnity of $80,000 to the United States and made a similar payment to

Great Britain.

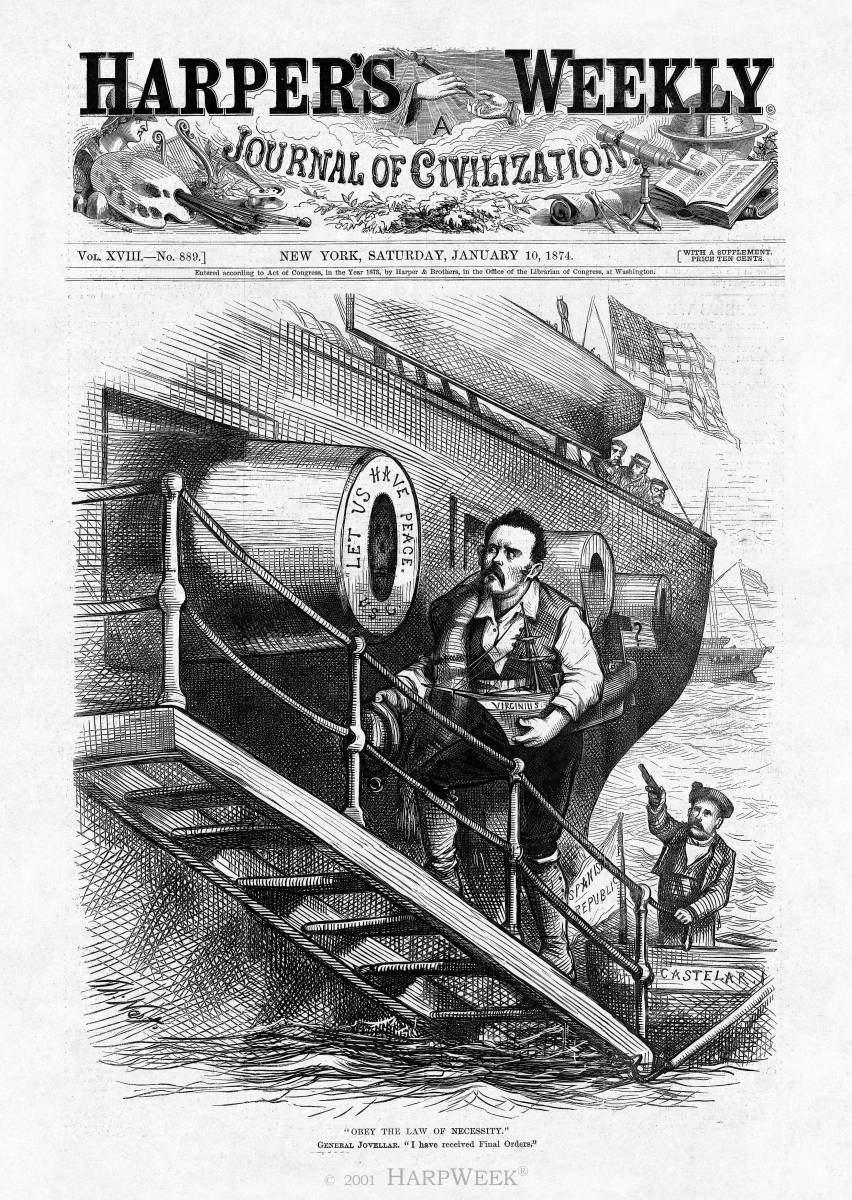

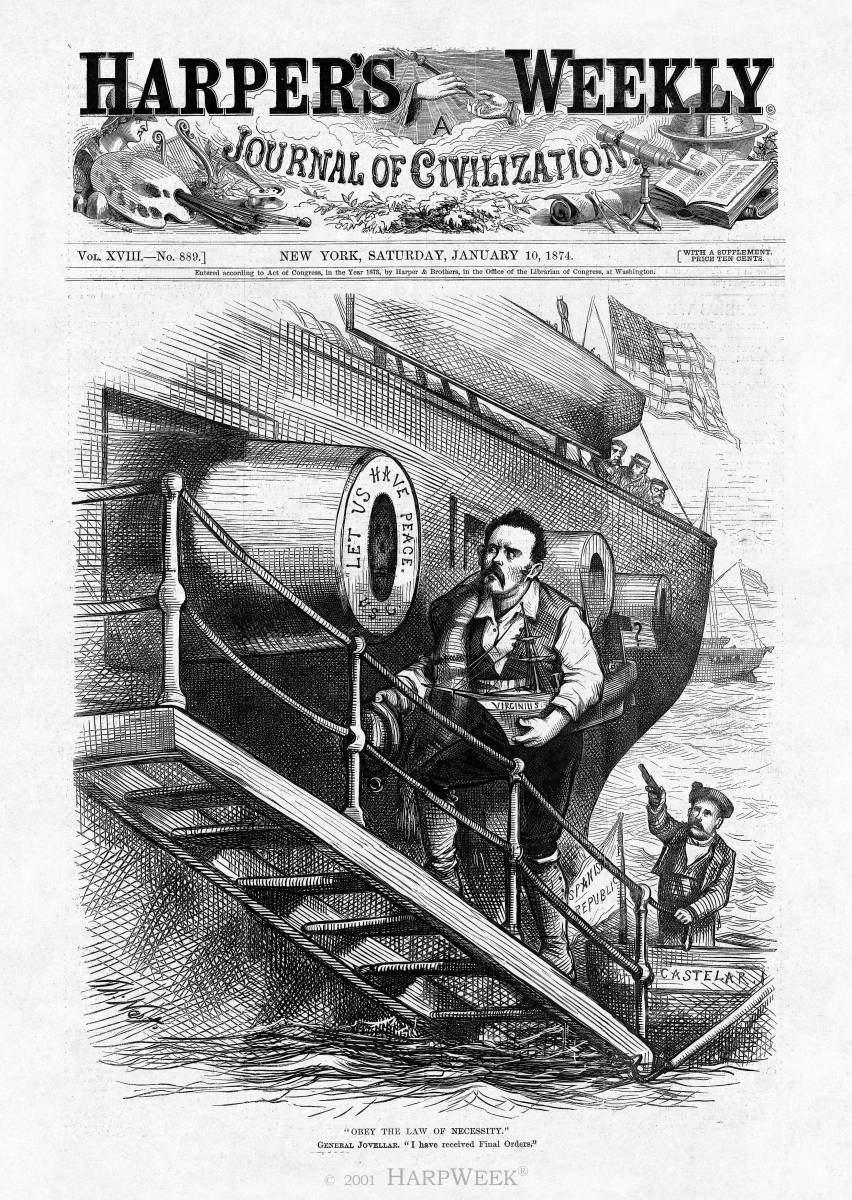

In this Harper's Weekly cartoon, Spanish president Emilio Castelar forces

General Joaquin Jovellar, the chief Spanish military official in Cuba,

at gun

point to return the Virginius to American authorities. The general stares

fearfully into the skull-emblazoned barrel of a cannon etched paradoxically

with "Let Us Have Peace," the slogan of Grant's 1868 presidential campaign.

On board the massive American vessel are (left to right): Secretary of

State

Fish, President Grant, and Navy Secretary George Robeson.

Although American tempers were inflamed, there did not seem to have been

a

deep and lasting desire for war during the Virginius Affair. One reason

was

that the Spanish monarchy had briefly given way to a struggling republic

(September 1873 - January 1874), with which Americans could identify.

Another was that Americans became distracted by an economic panic which

the United States was experiencing at the time. Perhaps most important,

though, was the war-weariness still evident in the aftermath of the Civil

War.

Such would not be the case two decades later. In 1895, another war for

Cuban independence began, leading to the Spanish-American War of 1898

and the subsequent establishment of an American protectorate in Cuba.